Tune into the full interview for more behind-the-scenes above or on Spotify or Apple

00:00–4:14: Show, episode, and guest intro

4:15–5:00: What is Cache Depot

5:00–7:40: The aha moment that inspired Cache Depot

7:41–10:47: How Ivan and Kaya Yiu’s career pivots prepared them to start Cache Depot

10:48–15:34: How Ivan and Kaya Yiu created and tested their MVP before going all in on the idea

15:35–16:47: How Cache Depot’s first customers helped them identify what was needed to build trust

16:48–19:30: How Cache Depot has garnered and maintained five-stars across all its Google Reviews

19:31–21:22: How exactly does Cache Depot differ from traditional self-storage providers

21:24–23:17: Why the City of Vancouver investigated self-storage facilities and what its amended zoning bylaws entail

23:18–23:58: The hidden fees imposed by traditional self-storage providers

23:59–25:12: Why Ivan and Kaya Yiu believe no one had yet to provide an alternative like Cache Depot

25:13–26:54: Nearly 70% of Cache Depot customers are first-time storage users who say they likely wouldn’t have used storage otherwise

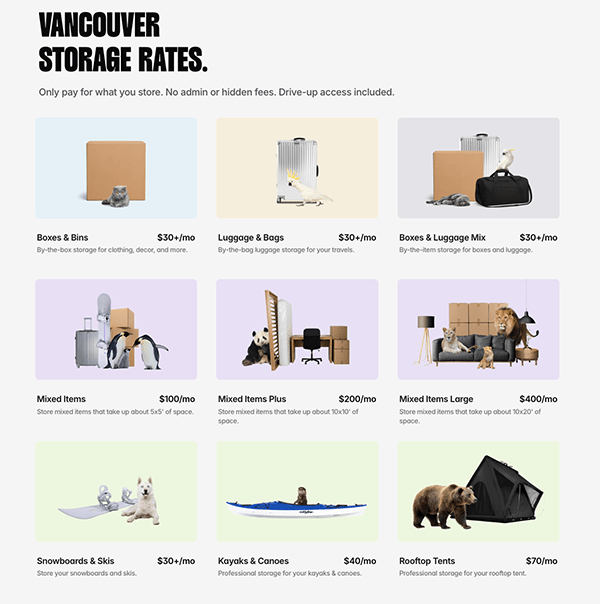

26:55–28:41: The trial-and-error process of developing a pricing structure that was simple and easy for customers

28:42–30:41: How exactly Cache Depot’s system works once customers bring in their items

30:42–35:02: The biggest problems that Cache Depot is solving for cities, customers, and even businesses

35:03–39:45: Early lessons pivotal to Cache Depot’s growth, from driving website traffic to finalizing branding

39:46–42:08: Cache Depot’s development plans for its app and expansion throughout Vancouver

42:09–43:41: Advice for other early stage founders

When Ivan and Kaya Yiu were looking for storage in Vancouver, they found themselves visiting multiple facilities just to accommodate a single four-seater. It was a frustrating and expensive experience. Companies suggested placing the couch on its side—which wasn’t even possible—or disassembling it. So, the couple ended up renting a 5x10 unit, costing around $300 a month, all for one piece of furniture.

With more than half the unit sitting empty, the Yius considered adding more belongings but didn’t want to force it. Ivan then had the idea of storing the couch at the warehouse where he worked, since they were downsizing and had extra space. It hadn’t been done before, but the owners agreed.

That greenlight sparked another idea from Kaya. Sensing they weren’t the only ones in need of an alternative—especially with how active platforms like Facebook Marketplace are for selling or giving items away—she suggested letting others benefit from their arrangement.

“I was a little hesitant,” admits Ivan. “My first thought was no one’s going to trust us [...] Kaya mentioned Airbnb, and obviously, I know what it is, but I never really thought about the fact that you’re paying to stay in a stranger’s home or vice versa, right? I was like, you know what, if people are okay with that, this is definitely a step down. People would be okay with this.”

What also convinced Ivan was knowing how little had changed in the self-storage industry over the past few decades. Most providers in Vancouver still follow a model built in the 1950s, where customers are boxed into renting units priced between around $150 and $475 a month (5’x5’–10’x15’)—the highest range per square footage in Canada. And that’s just the base cost. Extra fees often pile up for setup, move-in dates, and even the unit’s placement—whether it’s on a certain floor, near an elevator, or positioned to the left, center, or right.

Market snapshot: From “risky niche” to “hot commodity”

As self-storage rental rates remain unregulated, prices have soared as the business shifted from a “risky niche” to a “hot commodity” for its high returns and minimal overhead.

In 2019, the city began to investigate the impact after a record surge of facilities opened across Metro Vancouver. Two and a half years later, the city amended its zoning bylaws, which banned the construction of new projects in industrial areas near transit.

While the aim was to prevent inefficient land use and price escalation, a report in 2024 on the storage boom across Western Canada showed the regulations didn’t curb development in Vancouver; they pushed it into the city’s southern neighbourhoods, where many facilities already existed.

Another report in 2025 highlighted that B.C. is building more new storage than any other province in Western Canada, with projects continuing into 2028. A month after its release, an analysis found that B.C.’s supply had already far exceeded demand.

Cache Depot would discover the gap in Vancouver wasn’t because there was less of a need for storage. It was that the traditional model doesn’t work for many.

To test the demand for an alternative, the Yius created a landing page as their MVP and shared it through Craigslist ads. They found that locals were searching for more affordable and flexible storage. Like the couple, they didn’t want to pay for unused space, were offered options that weren’t ideal—like having kayaks stored outside even during poor weather—or were simply turned away by other providers. So, the Yius founded Cache Depot: a self-storage service that ditches the traditional model.

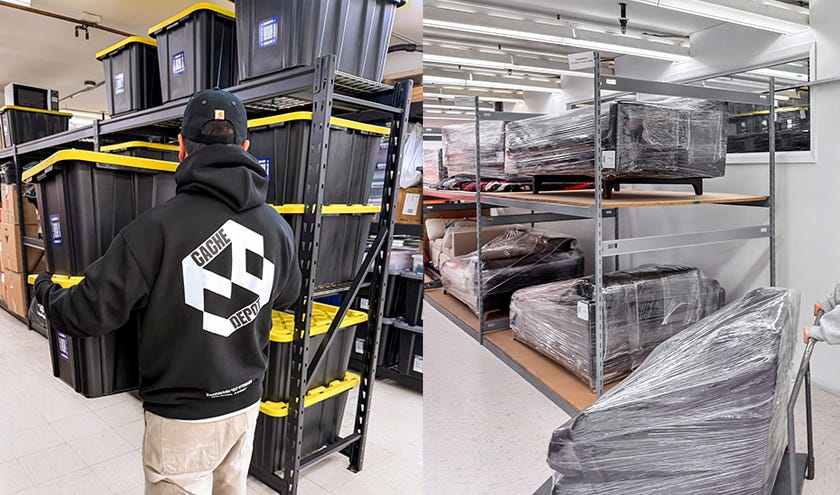

The company operates from a renovated climate-controlled warehouse. Imagine IKEA: extremely organized, clean, and modern, but private from the public and equipped with security cameras and sensors throughout the space. Every item is categorized, QR-coded, and placed on industrial shelves, racks, or pallets, then wrapped if needed. Instead of being boxed into units, customers can choose between paying per item, starting at $30/mo, or for the space their belongings actually take up, starting at $100/mo. Either plan can be canceled at any time. Pick-up and drop-offs can also be arranged through its moving service.

This is the story of a former warehouse director for brands like Canada Goose and Arc’teryx and a game designer behind a top 10 App Store hit are reinventing the storage industry, and their journey of finding customers on Craigslist and convincing them to meet in back alleys, to now growing its users by over 150% and monthly revenue by over 152% compared to last year, while maintaining five-stars across all its Google Reviews.

From Craigslist to a Custom App

Launched in 2023, Cache Depot has come a long way from its scrappy days. The self-funded startup is now developing an app to streamline the intake and retrieval process. Users will be able to receive instant quotes, view their belongings, manage subscriptions, and schedule pick-ups and drop-offs.

Cache Depot also plans to expand across the city by renovating warehouses instead of building new ones. The goal being to grow slowly without risking their capital while minimizing their urban footprint.

“Permits to build new storage facilities were heavily restricted because they take up valuable land that could be used for housing, employment opportunities or other essential urban development,” underscores Ivan. “Any new facility needs to be mixed use, with the ground floor being used for other things like retail, food, or drink instead of storage.”

Those regulations have inadvertently made Cache Depot more attractive. The warehouse sits on the ground floor with drive-up access through a bay door. Vehicles can pull up directly, and the team handles drop-offs and pick-ups at no additional cost. Meanwhile, other providers require navigating long hallways and multiple floors, and charge higher rates for units closer to entrances. The Yius predict those with drive-up access will increase their prices as there will be “less and less of them” because of the city’s policies.

When asked why no one else had yet to offer a solution like Cache Depot, Kaya explained that many providers are owned by real estate investment trusts. Because they make money by owning and leasing property, their focus is typically on maximizing value rather than improving the customer experience.

“A lot of the time when we’re talking to customers, they would say things like, ‘If we didn’t know about you guys, I don’t think I would have even used storage in the first place,’” says Kaya. “There’s an emerging market that’s very much underserved.”

She adds: “Another thing is, what we found through talking to customers is that 60 to 70 percent of them are first-time storage users. That further validates the fact that there are a lot of people out there who would use storage, but they don’t want to use it as it is now.”

Beyond personal belongings, some are starting to look to Cache Depot for their business needs as well. One entrepreneur was in need of a unit to plug in a fridge for their food products but couldn’t find any with an outlet. Leasing a warehouse wasn’t possible either, as they were still getting their venture off the ground. The company’s model let them get out of the “catch-22” of starting a venture with limited funding.

“Luckily, even though the building doesn’t look like much from the outside, because of what was stored there previously, there’s been a lot of care taken on security, energy, and electricity, and everything. So, it’s very well positioned to serve [food products] as well.”

Pivots That Prepared Them

Reflecting on Cache Depot’s growth, the Yius credit their first customers, especially the hesitant ones. Their feedback helped quickly identify what was needed to build trust, like showing them the warehouse so they could see every item was handled with care. Following up on whether they had additional questions was also valuable. It created more chances to explain how the business works and help people feel more at ease with the new concept.

The couple’s career pivots also played a key role in preparing them to start Cache Depot. Ivan, who pursued fashion design out of a passion for streetwear, over time realized he didn’t enjoy making clothes as much as he thought. When his employer needed support at their warehouse, he stepped in and worked his way up to becoming a director. It ended up partnering with major brands from Canada Goose to OVO and Arc’teryx. And while Ivan described the experience as “hectic,” he loved managing all aspects of what he felt was such a “slept-on area.”

“In clothing manufacturing, the warehouse is often completely overlooked,” he shares. “I always felt like the general attitude was, ‘The warehouse will figure it out,’ without much thought given to how complex and high-stakes that really is. We were holding goods worth millions, and it was up to us to keep everything organized, safe, and moving behind the scenes.”

Ivan adds: “That’s why I think it deserves far more attention and credit than it usually gets. We were always the underdogs, just quietly keeping things from falling apart. I liked that. It’s the same feeling now with Cache Depot: we’re small, doing things differently, and trying to prove there’s a better way.”

As for Kaya, her career began in programming, specializing in natural language processing (NLP). She moved from Vancouver to New York to intern at Morgan Stanley, where she built large-scale financial systems. Afterward, she joined Bloomberg to develop sentiment analysis algorithms—tools that categorize text by detecting the underlying emotion. She eventually decided to return to Vancouver and get into game design, as most opportunities in NLP at the time were research-based and required staying in the U.S. to advance. Notably, one of her projects reached the top 10 in the App Store with over 200,000 downloads, which, she says, transferred to knowing how to build other products.

“Whether it’s a game or storage platform, the goal is to make people feel something before they even become a user—or not,” she explains. “You have to also keep in mind you don’t have much time to capture the attention of your target audience. Potential customers scan, not read, web text in the same way players skip boring trailers or game tutorials. Short-circuit the distance between action and feedback whenever you can.”

Early Lessons & Takeaways

Looking back on lessons learned from building Cache Depot, the Yius began with underestimating marketing, initially believing that “if you build it, they will come.”

“When you’re building a game, you have certain platforms that will help you, like Steam or the iOS store,” shares Kaya. “If you get posted on the App Store, you’re pretty much all set. When it comes to marketing, your game will either pick up or not, and you will know immediately. Whereas with [Cache Depot], marketing yourself is a constant effort. You constantly have to adjust and teach people.”

Creating a visually strong brand through the website was also tricky, as the Yius didn’t have the experience to know what “good” looked like. They kept making a change, waiting a few weeks, and then iterating again. The couple admits they’ve had to remind themselves to commit to a design and let it breathe to see how customers respond before going through the process again.

What also went through many versions was figuring out the pricing structure. At first, Cache Depot let users choose individual items to add to a basket, but that created ongoing work for the Yius and decision fatigue for customers. So they shifted to having people select by item size—regular, large, and extra large—and introduced bundles, like five regular items for $55.

“A regular item would be anything you can carry yourself, just to simplify it,” explains Kaya. “So if it’s a box or a bike, you don’t really need to sit there and be like, ‘Okay, I need to measure out my box or bike,’ or check how much it weighs. It was one of those things where heuristic, I think, plays a good role in this.”

When asked what advice the Yius would give to founders starting or growing their business, Kaya encourages trying things without knowing exactly where they’ll lead: “Everything unfolded in a very specific way where if you asked me, what would I be doing today, five years ago, I would have no idea. So maybe give yourself some freedom to experiment. I think that’s important. If something’s on your mind that you really want to try, just do it [...] If it doesn’t work, what’s the worst thing that can really happen?

Ivan reminds others of the advantages that come with being a startup: “When we first started, I was very self-conscious that we’re this small company [...] As we grew and I talked to customers, my confidence grew with it [...] My advice would be to take ownership that you’re small, because you can do things that really put yourself in a different league. You can literally do anything you want. That would be my biggest advice because that was my biggest fear.”